Ceres harbors homegrown organic compounds

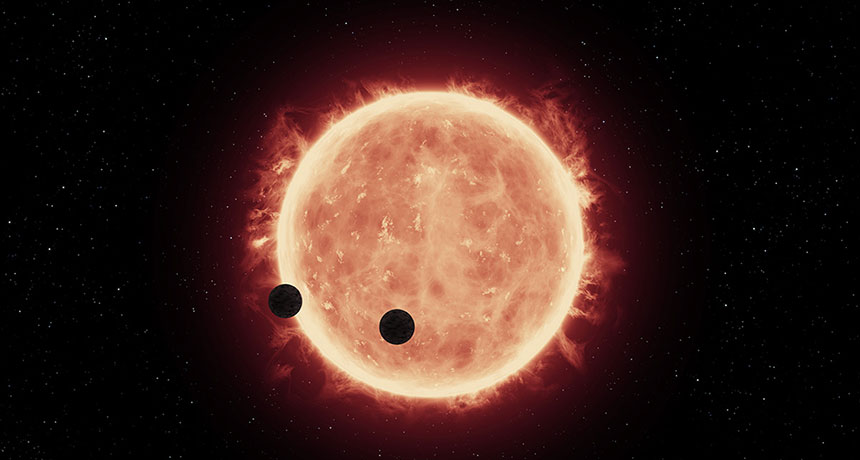

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft has detected organic compounds on Ceres — the first concrete proof of organics on an object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

This material probably originated on the dwarf planet itself, the researchers report in the Feb. 17 Science. The discovery of organic compounds adds to the growing body of evidence that Ceres may have once had a habitable environment.

“We’ve come to recognize that Ceres has a lot of characteristics that are intriguing for those looking at how life starts,” says Andy Rivkin, a planetary astronomer at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., who was not involved in the study.

The Dawn probe has previously detected salts, ammonia-rich clays and water ice on Ceres, which together indicate hydrothermal activity, says study coauthor Carol Raymond, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

For life to begin, you need elements like carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen, as well as a source of energy. Both the hydrothermal activity and the presence of organics point toward Ceres having once had a habitable environment, Raymond says.

“If you have an abundance of those elements and you have an energy source,” she says, “then you’ve created sort of the soup from which life could have formed.” But study coauthor Lucy McFadden, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., stresses that the team has not actually found any signs of life on Ceres.

Evidence of Ceres’ organic material comes from areas near Ernutet crater. Dawn picked up signs of a “fingerprint,” or spectra, consistent with organics. The pattern of wavelengths of light absorbed and reflected from these areas is similar to the pattern seen in hydrocarbons on Earth such as kerite and asphaltite. But without a sample from the surface, the team can’t say definitively what organic material is present or how it formed, says study coauthor Harry McSween, a geologist at the University of Tennessee.

The team suspects that the organics formed within Ceres’ interior and were brought to the surface by hydrothermal activity. An alternative idea — that a space rock that crashed into Ceres brought the material — is unlikely, the researchers say, because the concentration of organics is so high. An impact would have mixed organic compounds across the surface, diluting the concentration.

Detecting organics on Ceres also has implications for how life arose on Earth, McSween says. Some researchers think that life was jump-started by asteroids and other space rocks that delivered organic compounds to the planet. Finding such organic matter on Ceres “adds some credence to that idea,” he says.